Even journalists have privacy rights

Federal departments too often circulate the identities of reporters filing freedom-of-information requests

Journalists are sometimes in the business of keeping secrets.

They have a duty to protect the anonymity of their sources and contacts, and can even serve jail time if a court rules against their silence.

They also safeguard their own identities for certain investigations. A reporter might go undercover to observe a story from the inside – infiltrating a neo-Nazi group, for example – and hide the true purpose until publication.

There’s another situation in which journalists have a strong interest in anonymity; that is, filing freedom-of-information requests.

Research has shown that Access to Information Act requests to federal institutions from members of the media are subject to special treatment, at one time called amber-lighting. Their requests are flagged as sensitive, prompting communications specialists to stick their fingers in the pie. Message manipulation by flaks adds to already onerous processing delays.

Access-to-information units in various departments collect data about who is sending them requests. They tag them as coming from business, the public, academics, the media and others. The statistics are partly aimed at discovering who is using the law. But knowing the source of the request also informs the decision to classify some as sensitive, triggering that extra layer of vetting. Flagging media requests as sensitive is almost automatic.

Government officials argue that it’s only fair that ministers get a heads up about potentially embarrassing information releases, so they can respond in Parliament and elsewhere. Even the information commissioner accepts this as normal practice, but cautions that any such communications vetting must not bog down the processing.

The name and precise affiliation of the requestor (e.g., Jane Doe of the CBC) is supposed to remain confidential inside these units and not casually shared with the rest of the institution, except under limited circumstances. But we know identities do leak out.

I experienced an anonymity breach many years ago when I filed requests to the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency, based in Moncton, N.B. Suspicious that the agency was targeting me in some way, I filed an access-to-information request for any records that contained my name. About 500 pages landed on my desk.

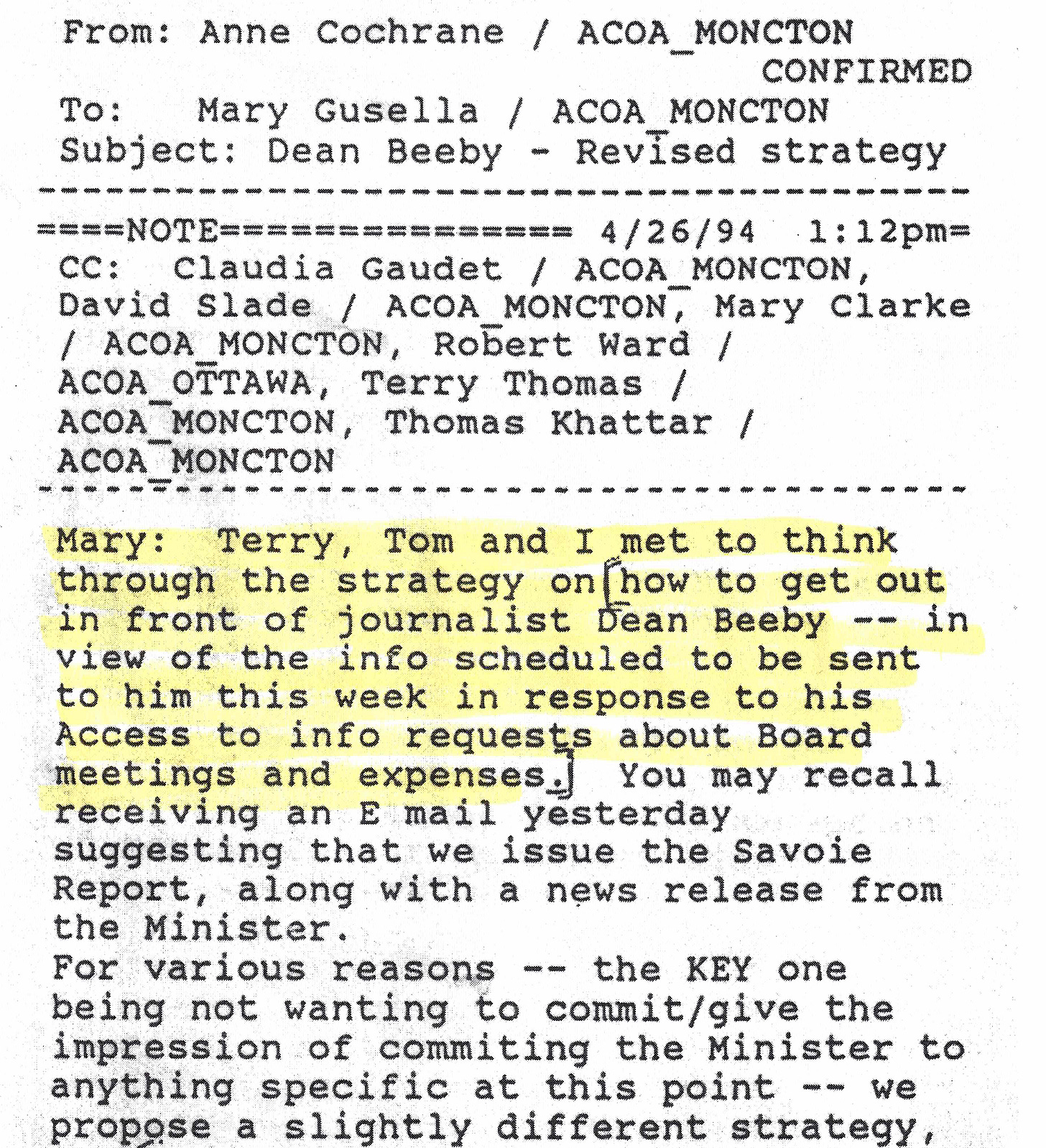

Sure enough, I found that my identity was indeed being shared casually within the institution. Worse, I learned that top executives were concocting strategies to blunt the impact of my reporting prior to releasing access-to-information packages to me. Here’s an example of how they planned “to get out in front of journalist Dean Beeby …”

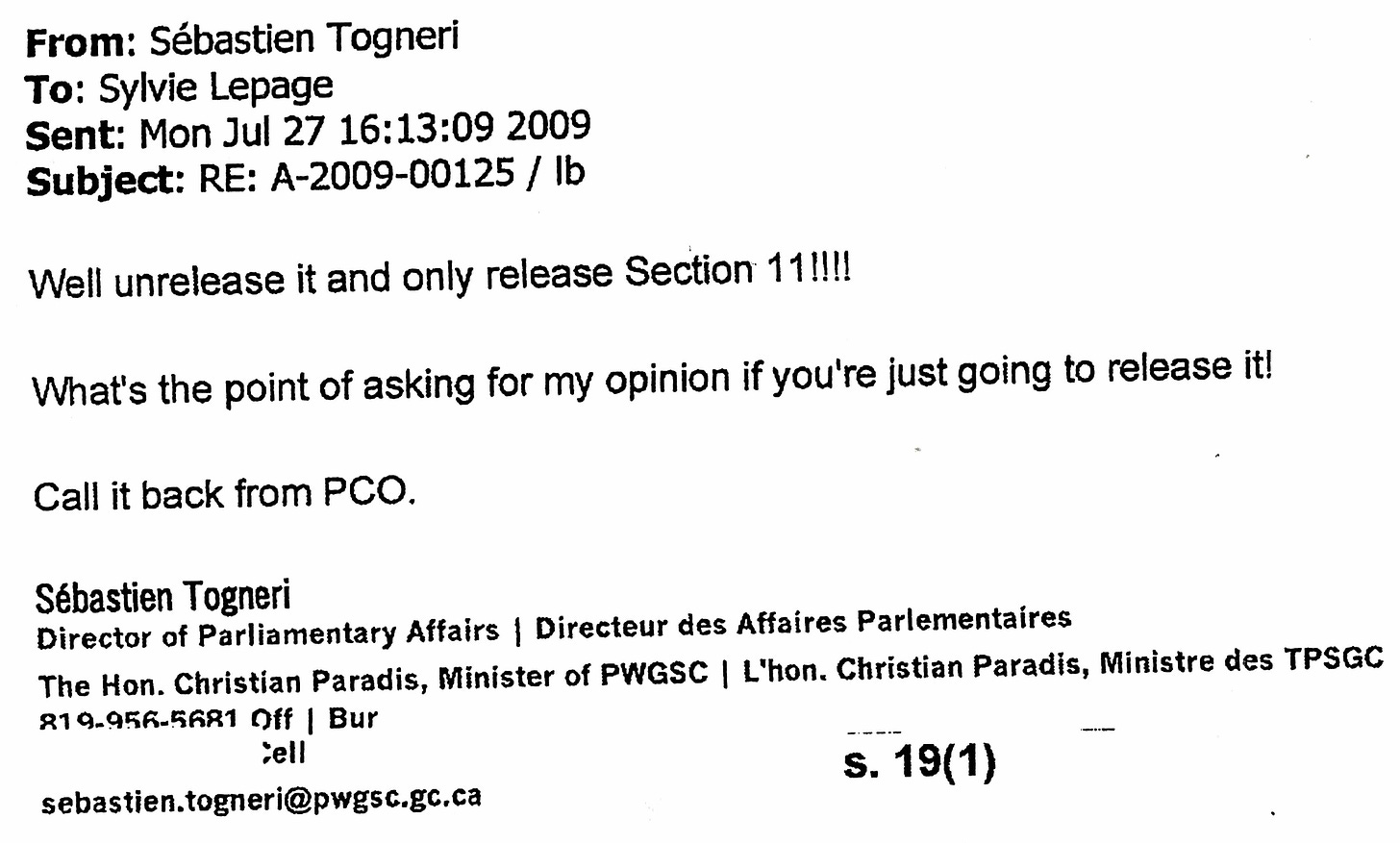

A more egregious incident occurred in 2009, after I had filed an access-to-information request to Public Works and Government Services Canada for a report on its real-estate holdings. My request was labeled sensitive, and shared with the minister’s office. An aide in the office ordered the access unit to withhold most of the report from me, even though the access officers had determined I was entitled to all of it. I only discovered this mischief after filing an Access to Information Act request for the 1,000-page processing file, where the interference was well documented.

Then-information commissioner Suzanne Legault investigated, and filed a special report to Parliament on the first-ever documented case of political interference in an access-to-information request. I never determined whether my name had been leaked to the minister’s aide, but my media affiliation certainly was.

Whenever I relate these stories at journalism workshops, people suggest having a third party – a neighbour or a friend, say – file requests on my behalf, thereby concealing my name and affiliation. My answer is that eventually the access units would figure out the media link to me, after seeing my stories published, so it was a futile strategy. Besides, I argue, my name might be a safeguard against bad behaviour. Access officers would know they’re dealing with a knowledgable requester who would insist on his rights.

Some years later, the federal government began to require requesters to self-identify as media, business, academic and so on. You could not complete an online request without ticking off one of these boxes. Some departments also required the requester’s date of birth, while others required an honorific (Mr., Mrs.. etc).

I and others complained to the information commissioner. The Access to Information Act (in a 2006 amendment) requires institutions to process requests “without regard to the identity of a person making a request.” The information commissioner in 2016 opposed the collection of this identifying information. Today a requester can tick off a box that says “Decline to identify” on the section that asks the category of requester. I always check that option.

In Europe, journalists have been intimidated or killed because they were outed after filing freedom-of-information requests. Those are extreme examples, but there’s a broad spectrum of roadblocks governments can erect to thwart investigative journalists whose identities are disseminated through the bureaucracy.

We’ll likely never end the privacy breaches outright, but there are two ways to fight back.

First, journalists should use freedom-of-information to access the processing file for requests where they believe they’re getting unwanted special treatment. Then with the evidence at hand, they can file a formal complaint.

Second, oversight bodies, such as the information commissioner’s office or Parliamentary committees, should conduct regular audits to determine whether “sensitive” files are being delayed or are subject to political interference.

Journalists have the same privacy rights under the Act as all other Canadians, and are not asking for special treatment. In fact, we’re trying hard to avoid special treatment.