How the rich captured a Canadian prime minister: Part I

New archival details about secret funds for William Lyon Mackenzie King

Vladimir Putin’s Kremlin and Donald Trump’s White House have shown how political leaders who bond with billionaires can be toxic to the public good.

Canada so far has avoided devolving into a plutocracy, but some of our past leaders have nevertheless been compromised by powerful men bearing suitcases stuffed with money.

Several prime ministers have accepted generous handouts from business titans over the years, though none so brazenly as William Lyon Mackenzie King (1874-1950), Canada’s 10th prime minister.

King’s personal worth was secretly goosed from modest in 1923 to princely by 1929, as a gilt-edged roster of Canadian business tycoons showered the new prime minister with cash, bonds, stocks, silverware, fine china and much more – transforming a man of ordinary means into a bona fide millionaire over a few short years.

The exact sources of this shady largesse, as well as its full dollar value, have been poorly reported in Canadian history texts, partly because the rich know how to cover their tracks.

But previously untapped files at Library and Archives Canada finally provide a grand tally – and the identities – of King’s monied benefactors. The details raise troubling questions about just what the rich stood to gain from their generous gifts to the country’s longest-serving prime minister.

King grew up in a financially strapped family. A hard worker, he was a diligent student, eventually a PhD at Harvard. He joined the federal public service in 1900, soon to become a deputy minister.

In 1908, he became a Liberal member of Parliament and joined the cabinet. Talent-spotters and friends ensured he became Liberal leader in 1919, returning the party to office in the 1921 election. He had power but no money. That soon was to change.

King’s lucrative decade of wealth accumulation kicked off in 1921, with the death of Zoe Laurier, wife of King’s beloved mentor, Wilfrid Laurier, the former prime minister who died in 1919. Zoe willed the couple’s home in Ottawa to King personally.

Laurier House, as it was known, was a shambles. King’s sensible friends suggested tearing it down and rebuilding, but sentiment for Laurier prevailed. King preferred that the brick home in the Sandy Hill neighbourhood – acquired by rich friends for Laurier in 1897 for $9,500 – should be preserved, renovated and refurbished. Alas, King’s salary of $10,000 left him no margin to do so.

Zoe’s gift thus became a catalyst for Canada’s business elite, who rallied to underwrite the costly upgrading. Originally estimated at $30,000, a full accounting in King’s papers shows the Laurier House renovations grew to more than five times that figure.

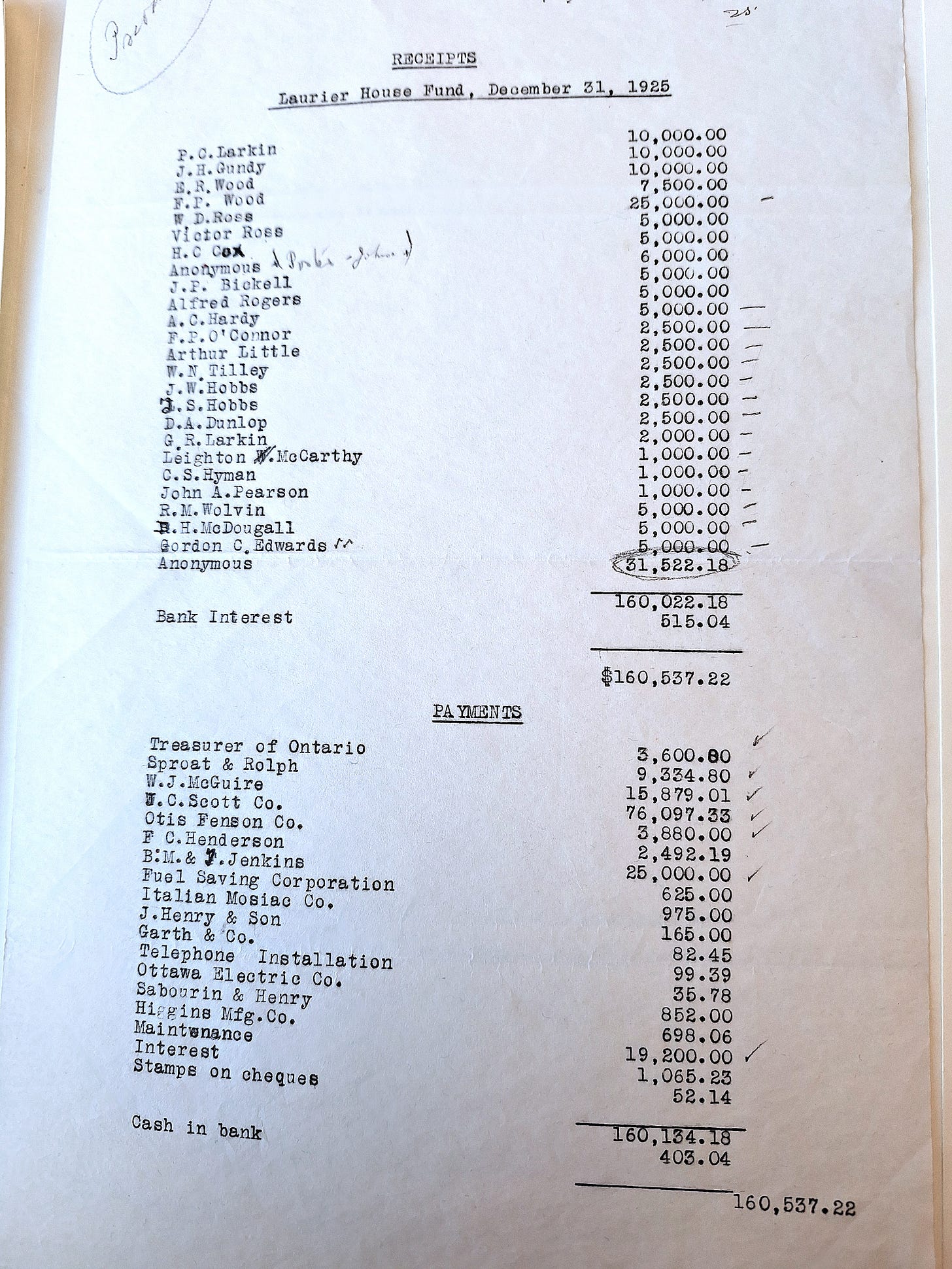

A Dec. 31, 1925, balance sheet shows more than $160,000 was spent on architects, carpenters, electricians and others, a budget-busting makeover worth about $2.8 million today.

The accounting also names 23 Canadian businessmen who paid for those renovations, and two mystery donors listed as anonymous. Heading the roster was Peter Larkin, the Salada tea magnate and King’s close friend, who chipped in $10,000 and helped marshall the contributions of fellow business titans.

“I tremble to think of what the ‘Commoners’ would think of their Leader amid so much grandeur,” King wrote to Larkin on Jan. 14, 1923, after spending his first night in the now-opulent mansion.

Larkin had supported King’s political career, and was rewarded with a 1922 appointment as Canada’s High Commissioner in London. On his way to the office each morning, Larkin would stop by the posh auction houses of Christies and Sothebys to order fine furnishings that would be shipped to King’s new Ottawa home.

Larkin, who complained it was “impossible” to maintain his own London mansion on $100,000 a year (about $1.7 million today), underlined to all benefactors that the house and its furnishings belonged personally to his friend, rather than to the Liberal Party. Larkin did not want the money going to “some indefinite person who may appear on the horizon a year, five or twenty years from now,” he told a prospective contributor.

Larkin wrote to King: “Of course all these things are for your own service and are your own property, including the silver. On every piece of the latter your initials will be engraved.” King replied: “I shall ever feel a deep obligation to you.”

The two busy men carved out time to exchange detailed home-decorating ideas: where to put furniture, layout of the library, what art should decorate the walls. After all, King needed an elegant, stately home at which to entertain visiting dignitaries, and the prime minister had no wife to help him.

Larkin also micromanaged the architects, insisting, for example, on a blueprint change that would put two electric lights in each bathroom. “There is nothing so provoking as not to have good light on both sides of the face when shaving,” he said.

Through it all, King was kept aware of which captains of industry were picking up the bills – bankers, manufacturers, investment dealers, mercantilists. In a letter to Larkin, the prime minister called the largesse “manna” from heaven. More manna was on its way.

Larkin saw Laurier House as a white elephant that King – “with no financial resources,” as he put it – could ill afford. “I am afraid we are very much like the generous man who presents a Rolls Royce car to a fellow with a limited salary.”

Larkin wrote to well-heeled banker William Ross, who contributed $25,000 to the renovations: “I do not believe our friend can live in that house in an easy frame of mind on his income.” (King later handed Ross a patronage plum, appointing him lieutenant governor of Ontario.)

Larkin set about creating a trust fund for King that would underwrite his new lifestyle. He enlisted Ross as bagman, since Larkin’s job as High Commissioner in London kept him out of the country. The goal was to create a big enough nest egg to generate $7,000 to $10,000 of income each year.

Tomorrow: Part II - The trust fund that made King a millionaire.