Hubris and survival in the news industry

Oral history chronicling the demise of the Village Voice has lessons for Canada

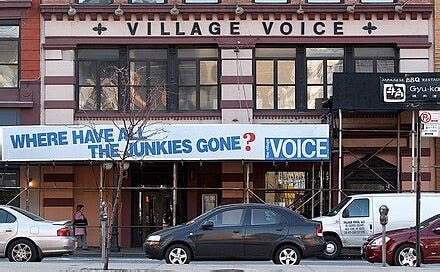

A new oral history of the Village Voice, the weekly rag that goosed American journalism for decades, is a pungent, bubbling wort of a book.

Author Tricia Romano didn’t write the text for The Freaks Came Out to Write. Instead, she patched snippets from more than 200 interviews with veterans – no, make that survivors - of the newspaper that thrived in the grunge-grid of a Greenwich Village ignored by the stodgy New York Times.

The pastiche format should not work, but Romano succeeds masterfully. Each short chapter is themed, and the gossipy narrative flows deliciously, from the Voice’s founding in 1955 to the sad shambles it became after the turn of the millennium.

Dwight Garner’s admiring account in the New York Times is buoyant, reflective of the book’s tone and rich content. I won’t attempt to better the most entertaining reviewer in America.

But there’s a section of Romano’s book that Garner barely touches, which grabbed my attention. It’s about Craig Newmark, the inventor of Craigslist, the slayer of classified ad sections across North America.

The Village Voice specialized in spotlighting edgy culture, foregrounding the marginalized, and goading America with gonzo investigative deep-dives.

But the 4 a.m. lineups by readers to grab the first copies each Wednesday were about the apartment listings in the back of the “book,” as staffers called the paper. The titillating sex personals had another eager readership. Classifieds floated the paper for decades, bringing in more money per square inch than any display ad.

In 2001, the Voice hired a 20-something web developer, Anil Dash. The day after he arrived, Dash asked: “Hey, what are we doing about Craigslist?” Craig Newmark had developed the digital classified site in the late 1990s, and it was getting traction. His bosses’ answer: “Who’s Craig? What are you talking about?” Dash thought, “Oh my god, we’re screwed.”

As Craigslist began to eat into the paper’s classifieds section, and the bosses finally took note, the arrogant response was simply “we’ll just buy him out.” Anti-competitive, to be sure, and blithely dismissive of the existential threat.

The paper suffered through a string of ownership flips, bad managers and rapacious investors, which drained the talent pool and dimmed the vision. But the fatal misstep was ignoring those digital barbarians at the gate.

Of course, the Village Voice was not alone in its solipsism, so to speak. The same drama was unfolding in every city where legacy newspapers felt unassailable, including Canada.

The curious thing is that the Voice claimed it had its ear to the ground, as a kind of distant early warning radar, spotting trends before they were even called such. And yet a fledgling web developer saw the storm clouds gather even as the editors argued about which sado-masochist cafe to review in the next issue.

“I couldn’t tell people, ‘The whole world is about to change, and it’s these weird, janky-looking websites like Craigslist.’ I felt like Chicken Little,” Dash told Romano. “I was the only person in the office using Google.”

The lesson? Paradigm shifts on the scale of the digital revolution only dimly register with the old guard, especially at publications with comfortable, reflexively anti-competitive business models. And like tiny mammals scurrying at the feet of dinosaurs, the young often have a sharper sense of survival than their half-blind elders.

On that note, Anil Dash has prospered, becoming a White House advisor and head of digital start-up Glitch, among other ventures. The Village Voice carries on in emaciated form, easily ignored, no longer driving agendas. And all those Canadian newspapers that were also Craigslist road kill? They continue to rattle their tin cups in Ottawa, looking for bailouts.