The 10 men who have governed the Bank of Canada since its inception in 1934 have been taciturn types, studiously avoiding the mud-holes of public controversy. Central banks trade in trust, and must project immutability and stability.

That’s why it was so unusual in 2012 to hear Mark Carney, then governor of the Bank, apologize to Canadians for screwing up.

Disputes have dogged other governors. James Coyne resigned in 1961 after clashing with the Diefenbaker government. John Crow became persona non grata with the newly elected Chretien Liberals in 1993.

Those conflicts arose from genuine policy differences. Nobody apologized for anything. Carney’s mea culpa was different.

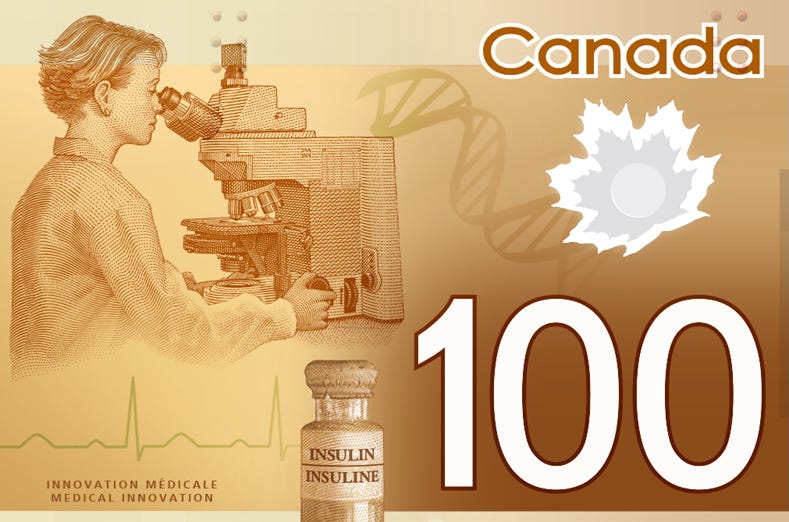

In 2011, the Bank of Canada introduced plastic bank notes into circulation, starting with the $100 polymer bill, which celebrated Canada’s medical innovations. Before releasing the $100 note, the Bank hired a firm to test drive the design with focus groups across Canada.

Through the Access to Information Act, I obtained the results of that exercise. The groups had been shown a mockup of the bank note, the reverse of which was illustrated with an “Asian” woman peering into a microscope.

“The representation of the woman as Asian leads to controversy,” warned the focus-group report from The Strategic Counsel.

As an example, the report quoted a participant in Fredericton: “The person on it appears to be of Asian descent which doesn’t rep. Canada. It is fairly ugly.” And in Montreal: “Pourquoi asiatique? Pourquois pas quelqu’un d’autre?”

The “Asian” woman disappeared from the actual $100 bank note that was issued in 2011, replaced by a Caucasian-looking woman. She’s still there today:

I wrote a story, quoting a spokesman who defended the swap by saying the Bank wanted the image to have “neutral ethnicity.” Whatever that means.

Three days later, Carney read a statement in Toronto to try to douse the controversy, which had upset Canada’s Asian communities. “I apologize to those who were offended - the Bank’s handling of this issue did not meet the standards Canadians justifiably expect of us.”

But it was a plea of guilty-with-an-explanation. The focus groups had been shown a photoshopped image based on an original photograph of a “South Asian” woman, Carney said. The image was never intended for the actual bank note. The final image used was created “so as not to resemble an actual person.”

Carney distanced himself from the mess, suggesting he was not privy to the “early design stages,” and approved only the final design. There was no mention of “neutral ethnicity.” Rather, Carney acknowledged that the image on the circulating $100 bank note “appears to represent only one ethnic group.”

I wanted to test the claim that the focus-group woman was “South Asian,” that is, from the region of the Indian subcontinent (somewhat narrower than the broader term “Asian”). So again using the Access to Information Act, I asked the Bank for a copy of that image. Officials baulked, so I complained to the information commissioner. Here’s what I finally received:

The face of the woman was withheld to protect her privacy, the Bank said. I wondered whether the Bank had secured her permission to show her face to the focus groups.

Indeed, I was never satisfied with any of the explanations - there were too many inconsistencies. Why would the Bank bother to gather reactions to an image never intended for the bank note? Why did The Strategic Counsel flag the “Asian” woman as a concern if she was just a placeholder?

So what does all this amount to, besides being fodder for biographies of Canada’s 24th prime minister?

Deduct points for a ham-fisted currency design process at the Bank of Canada. Give points for a swift apology from the man in charge. Deduct points for an obfuscating explanation.

Canadians can do the math for themselves.

___

Postscript: Speaking of math, the basket of consumer goods and services that could be bought with that $100 bank note in 2011 now costs $138.

Much appreciated, James, especially coming from an exacting craftsman himself. Journalism called, and wants you back.

I came for the pitch-perfect headline and narrative craftsmanship, but stayed for the redacted facial features. Hope you’re well.