Shackleton's last ship was a dud for polar exploration

The 1921-22 crew of Quest, located in the Labrador Sea this week, reviled the vessel

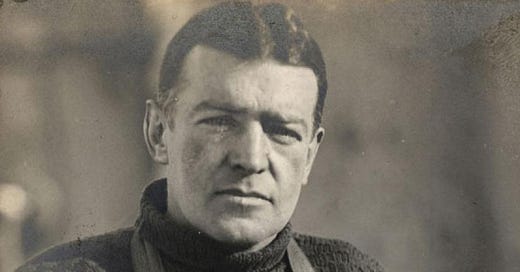

Sir Ernest Shackleton’s last expedition ship, which was located on the seafloor off Labrador this week, was reviled by his crew as badly built, cramped, underpowered and completely unsuitable for exploration in polar seas.

Quest was a “contraption of discomfort,” George Vibert Douglas, a Canadian member of Shackleton’s crew, complained in his journal on Feb. 2, 1922.

Days later, Douglas compiled a list of all the things he despised about Quest, a former Norwegian ship – originally christened Foca I – built of oak and designed for Arctic seal hunting.

The vessel was “the wrong shape and poorly built … [steam] Engines altogether too feeble and unreliable. … Rigging - the most awkward possible. … Vile accommodation - leaking decks and no place to work.”

“With the exception of the bridge most things on the ship are just as they should not be.”

Hubert Wilkins, an Australian naturalist and Douglas’s buddy on the crew, said the agent who bought Quest on Shackleton’s behalf must have been “drunk and seeing double.”

A cabin on the temperamental vessel was where Shackleton took his last breath on Jan. 5, 1922, before the expedition got under way.

Quest had dropped anchor the day before at Grytviken, a odorous whaling centre on South Georgia Island, bobbing in water red with blood and rotting whale carcasses. Shackleton had suffered a heart attack in Rio de Janeiro weeks earlier, and a second one killed him.

“We have lost a great leader,” Douglas wrote in his journal of the charismatic Shackleton, loved by all his crews for his empathy, dash and care for their well-being. Douglas designed the memorial cairn for Shackleton on South Georgia, where he was buried.

The expedition carried on under Frank Wild, himself an old Antarctic hand but with none of the respect the “Boss” so readily won.

Shackleton had an ill-defined plan to visit south polar islands and coasts, goals cobbled together after his original project to explore the Canadian Arctic fell through for lack of funding from the Canadian government.

Wild carried on with the temperamental Quest as best he could, burning coal too rapidly and stopping only briefly at a few islands, where Douglas grumbled he had little time to geologize.

Shackleton had hoped his would be the first Antarctic expedition to fly a plane, and took along a New Zealand pilot and Baby Avro aircraft. That is, Quest carried the fuselage, but not the wings and floats, which were to be picked up in Cape Town along with supplies such as warm clothing.

But Quest performed so badly during its trip south from England that it needed a month’s worth of major repairs in Rio de Janeiro (warped keel, bent propeller shaft). That meant skipping the Cape Town stop. Thus without wings, the Baby Avro would never become airborne.

Douglas, just 29, carried out as much geology as Wild’s caprice and impatience would allow. He called the trip a “futile attempt by grown up infants to reach the Antarctic Continent” – which they never did. “This senseless rummaging around putting in time is absurd.”

The trip was thus a last, sad gasp of the so-called Heroic Age of Antarctic exploration, in which legendary explorers such as Roald Amundsen, Robert Falcon Scott and Shackleton overcame enormous odds to pierce an unknown frozen continent.

Douglas’s brief time with Shackleton boosted his career, which ended in a long stint as chair of geology at Dalhousie University, in Halifax, before his death in 1958.

Quest reverted to seal-hunting after the expedition, and sank in the Labrador Sea in 1962. The crew was saved and the position noted, making it easier for the Royal Canadian Geographical Society-led project to locate it this week.

Douglas admired Shackleton, and appreciated the brief time spent in the south polar regions, despite Wild’s weak and indecisive command. But he and the rest of the crew had no warm feelings for Quest, one of the most ill-suited exploration vessels ever dispatched to Antarctica.

Dean Beeby is an Ottawa journalist, and author of In a Crystal Land: Canadian Explorers in Antarctica (University of Toronto Press), which drew on journals, diaries and other primary documents.