How the rich captured a Canadian prime minister: Part II

New archival details about the identities of Mackenzie King's benefactors

(Part I is available here.)

Peter Larkin launched King’s fund with $25,000 of his own cash, deposited Sept. 22, 1925 at the Old Colony Trust Co.’s main branch in Boston, the same firm used by Salada Tea for its U.S. operations. Likely he reasoned that a foreign account would reduce the risk of discovery.

Recorded as the Laurier House account, the assets were nevertheless in King’s name and under his control. The prime minister was given regular statements and a cheque-book. Old Colony confirmed in writing that the money was King’s “personal property.” He could withdraw, invest or buy new property. King did all of that.

William Ross was a mediocre bagman, so Larkin eventually took over fundraising. He was fabulously successful. A detailed tally sheet in the archives shows 17 business leaders and two corporations collectively pledged $250,000. Almost all had delivered the assets by the end of 1928.

The lone holdout was Joe Atkinson, president and owner of The Toronto Star, a Liberal party newspaper. Atkinson had promised $25,000 but was short on cash after paying for a new building and printing plant. He reneged. “[W]e have spent a great deal of money and I don’t know how long it will be before we get our head above water,” he disclosed to Larkin.

Even so, the Laurier House account brimmed with assets of $225,000 by early 1929, mostly in cash and bonds with a few stocks. King was over the moon. “It has gone away past anything of which I have ever dreamed,” he wrote. This was no blind trust. Larkin gave King the names of the wealthy donors, whom he called a “band of good fellows.” It was a who’s who of the moneyed class.

In appreciation, Larkin sent each donor a Charles II guinea, a relatively rare 17th-century British gold coin. Investment dealer Alfred Ames (who had put a paltry $2,500 into the fund) dubbed the group “The Order of the Guinea.” King’s five-guinea piece, a gift from Larkin, made him head of the order.

King was kept aware of Larkin’s progress in building the fund, and knew who was being approached. King kept donor lists, in his own crabbed handwriting. He spoke personally with contributors, thanked them profusely, avoiding written records of his gratitude.

Larkin confessed to King in February 1929 that “you are not supposed to know who are the subscribers.” But he had regularly violated that principle, sometimes coyly. “Our Montreal friend” in one letter referred to donor Wilfrid McDougald, whom the prime minister had appointed a senator in 1926. King was well aware in 1927 of McDougald’s initial $10,000 donation to the Laurier House account, and of McDougald’s final $15,000 tranche in 1928, which he called a “magnificent figure.”

The total of all contributions for renovations and for the fund was now at least $385,000 (or $6.7 million in today’s dollars), assembled in a mere six years.

Larkin’s further gifts of money and merchandise boosted the total. He had six brass bedsteads built expensively in England, and shipped to Laurier House. There was more English silverware, engraved with King’s name, and a “pearl pin.” Sir Wilfrid Laurier’s nephew Robert had failed to pay the 1922 city taxes on Laurier House, where he lived for a time. Larkin covered King’s unexpected $1,000 municipal tax bill, as well as the inheritance tax on the property. The grand tally to King’s benefit may never be calculated.

Larkin justified the handouts by arguing they were the opposite of bribes. Rather, they guaranteed King’s independence, he said. Otherwise the prime minister’s modest means would distract him from governing, and leave him susceptible to rich men seeking favours. He told King the donors expected nothing in return.

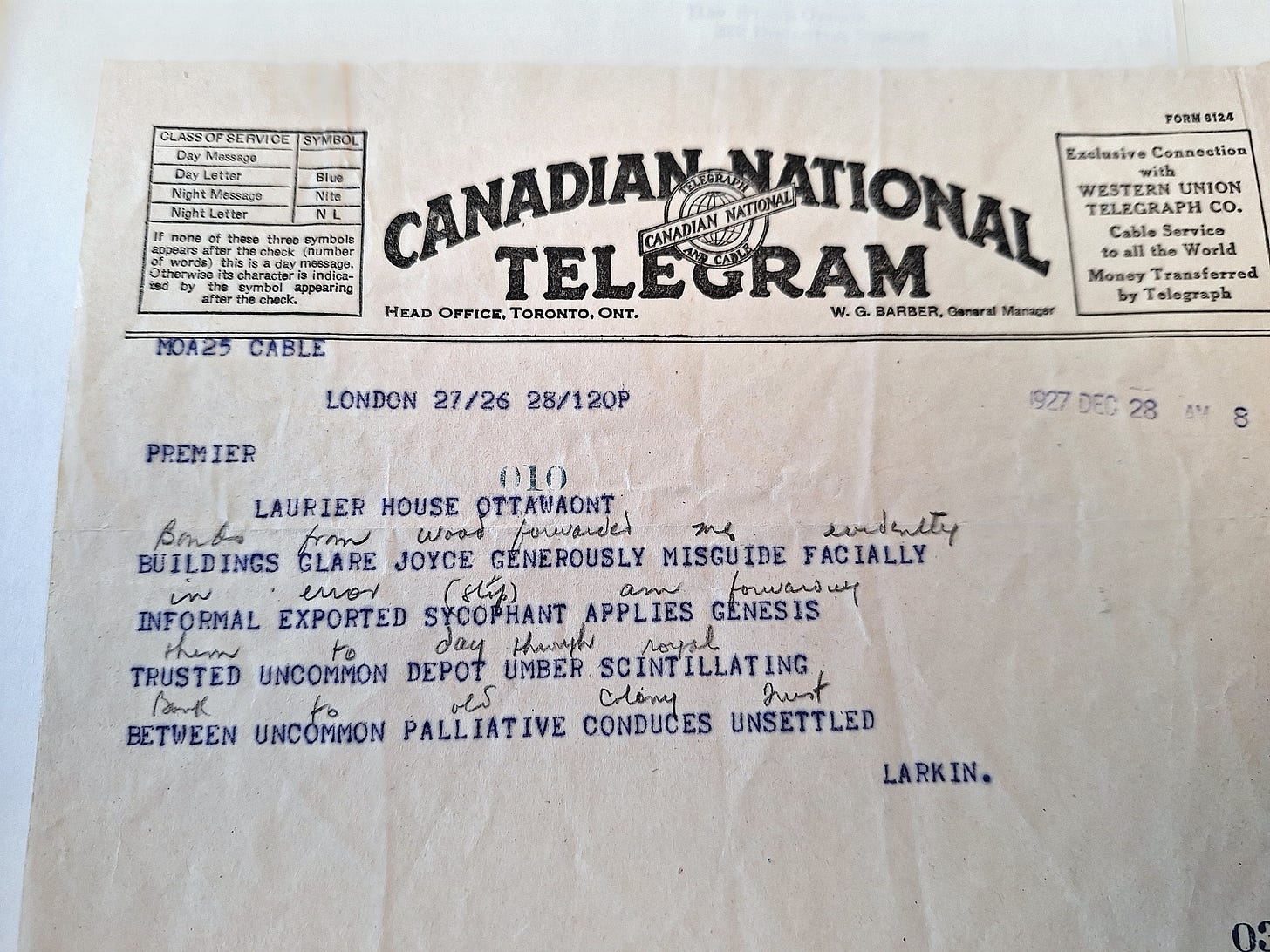

Precautions were taken to keep the Old Colony account secret. The King files include a 1927 transatlantic telegram (illustrated above, MG26 J11) addressed to him written in code, referring to financier Edward Wood’s recent $15,000 donation. Larkin asked McDougald to contribute only cash, to thwart a paper trail. Even so, rumours of the fund inevitably spread. In May 1929, the Toronto Star reported on its existence, without listing the donors, to no apparent controversy.

Such funds were not uncommon at the time, in Canada and in Britain. King’s justice minister, Ernest Lapointe, was set up with $100,000 by supporters, for example. But King’s political instincts told him that public knowledge about his silk-stocking backers could be dangerous. He wrote to Larkin in early 1929:

“I have wondered whether the fact that each contributor has the names of the others in his possession, and in a document which may fall into the hands of third parties, might lead to the entire list being given publicity, or to some of the names on the list becoming known, at a time and in a measure which might seem to occasion embarrassment to the Government or myself.”

The complex Beauharnois Scandal of 1931 stoked King’s worst fears. McDougald had profited from a 1929 cabinet decision, and King worried that “our Montreal friend” might spill the beans about the trust fund in testifying before a Parliamentary committee. McDougald never ratted, but King lost sleep. As a precaution, he returned $15,000 of McDougald’s money, though inexplicably kept the other $10,000. King always denied he had given McDougald any special benefit.

In 1925, when it wasn’t clear King would survive as prime minister, donors were “waiting … to see which way the cat jumps,” Larkin wrote. They preferred to support a head of government rather than a losing politician. King in fact did forfeit government in the King-Byng affair, but was returned to power in the Sept. 14, 1926 election – shortly after which the flow of trust donations resumed. King the prime minister, not King the man, was the coveted trophy.

The King papers at Library and Archives, and King’s own diaries, contain no obvious evidence of bribes, actual or attempted. But such neat quid pro quos may be too crass a metric for assessing influence-peddling. Certainly King rewarded Larkin and Ross, the two bagmen, with vice-regal appointments, but the salaries were pitiable and the positions had little power. Indeed, Ross got hammered by the stock-market crash of October 1929 and gave up his post as Ontario’s lieutenant governor because the pay was too low.

The real prize for a wealthy donor was having a prime minister in the pocket, someone alert to the special needs of business. A friend at the apex of government could bat down proposals that might harm profits. A powerful leader on the take would be an insurance policy against state measures damaging to commerce.

King’s secret dalliance with wealthy barons has drawn fire from some modern historians, a few suggesting bribery was in play. Others defend King, arguing there’s no smoking gun and trust funds then were commonplace. It’s unlikely we’ll ever see hard proof of any malfeasance that was hatched behind closed doors, in executive suites, corridors or gentlemen’s clubs. We’ll probably never know what favours, if any, were bought and sold. Consider that it has taken most of a century even to learn the names of the players.

One thing is certain: then and now, the fabulously wealthy typically want to insinuate themselves into government, believing that business acumen is a sufficient qualification for public affairs, and that their agendas are naturally in the best interests of the country. The Order of the Guinea is a timely reminder that Canada needs tough laws and regulations, open and accountable governments, and a thriving press, to keep them at bay.

_

This article draws primarily on records in Library and Archives Canada: MG26 J11 Containers 5 & 6; and MG26 J13 (King’s diaries, also available online).

The best modern biography of King is Alan Levine’s King: William Lyon Mackenzie King: A Life Guided by the Hand of Destiny (2011). See also Levine’s article for the Globe and Mail on secret funds and prime ministers.

My thanks to colleague Mario Possamai for invaluable research suggestions.

Thanks Juliet.

WLMK was indeed a nutter - and apparently only too happy to be bought. From what I have seen, the diaries touch only tangentially on the trust fund.

I remember my junior days at the CP Ottawa bureau when the archives would release a new set of cabinet minutes each year, based on the 30-year rule. I was assigned to the 1957-58 Diefenbaker cabinet minutes, along with Edison Stewart and one other. So much fun. The archives stopped this ritual a long time ago.

Thanks, Gerry. I also wonder what deals are being cooked up behind closed doors even today. And yes, Mario is first-class.